(5 minute read)

In the last three years, I’ve taught two teenage boys how to drive a car. Where I live in Texas it isn’t unusual for parents to teach their children to drive. However, it can be an emotional roller coaster as a parent, especially as your child is first learning and gaining experience. I had no idea it would teach me so much about naming emotions.

It’s week one and I’m sitting in the passenger seat, which feels strange to me with my son next to me in the driver’s seat. I’m anxious and he is too, but he’s doing his best to show that he is chill. In the beginning there are so many things to learn: use the turn signal, don’t give it too much gas, slow down! Please brake gently. Keep checking your mirrors and scanning around you. Coordinating all of these new skills is a real challenge!

I stop and recall that even before we got here, my sons had to pass a road rules test. They had to learn the names of different road signs and the basic rules of driving. At the beginning of any new activity, it’s usually important to learn the vocabulary that applies, just like a new driver learns that road signs have a systematic meaning based on their shapes and colors as well as the words on them.

Starting to Think about What I’m Feeling

I was in my thirties before I gave very much thought to the different words I use to describe my feelings. I was preparing to go on a business planning retreat for the company I worked for, and we were given some “homework” on naming emotions in preparation for one of the sessions.

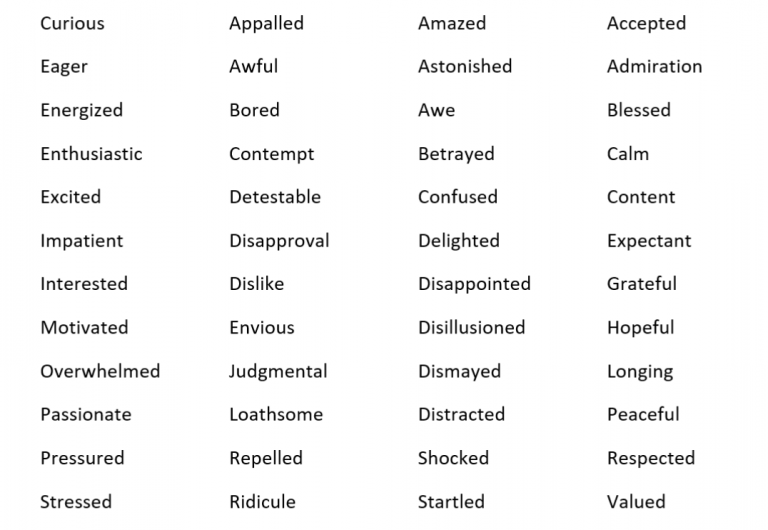

For two weeks I was supposed to take a short break in my day at set times (morning, noon, afternoon and evening) and write down what I was doing and what I was feeling. Four times a day I would log my emotions, and I was given a sheet with over 150 emotion words on it. I remembered it was a little overwhelming and seemed disorganized, but I did the homework and found it kind of interesting. It was the first time I could recall really thinking hard and repeatedly about what I was feeling and how to name it.

Since then I’ve learned that we don’t often use a wide range of words to describe our feelings. Besides “fine”, “okay” or “good” (which aren’t really feeling words–more on that later), the most common way we talk about emotions is surprisingly limited: I’m mad, glad, or sad, and that’s about it.

But there are more feeling words—so many more! Training ourselves to learn them and use them in naming emotions regularly has some very real benefits.

Naming Emotions - Why Emotions Need Names

I got by many years without consciously naming my feelings. Maybe you have too. Why do we need to name our emotions?

I’m an introvert and not especially outgoing in social settings. If there are a lot of people I don’t know, I don’t tend to mix and meet a lot of new people. In a group where I know a majority of people, I’m a different person. I greet people and tend to have numerous conversations.

I’ve noticed that there is a very real difference when I know people and can call them by name. Likewise, I’m embarrassed when I’ve been introduced or met someone before and I can’t remember their name. Knowing someone’s name gives me a familiarity and comfort around them and takes down the anxiety.

Maybe you don’t feel anxious (or you aren’t consciously aware of it). Think about the last time you were in a situation where you had very little knowledge. Maybe it was with friends talking about a show you hadn’t watched, or taking your car in for repairs or trying to get technical help online or on the phone. Perhaps you had medical tests run or you saw the doctor about an issue that you hadn’t read up on. When you don’t know the names of things or how they are related, you feel at a real disadvantage.

But is it really that simple? Just learn more feeling words?

Actually, it does make a difference. Matthew Lieberman and other researchers at UCLA found that using specific words to describe feelings (the technical term is “affective labeling”) tended to lessen strong or distressing emotions.

Common sense would say that focusing on our fear or anxiety is going to increase it. Lieberman’s research demonstrated the opposite. People who used the words “fear”, “anxious”, “anxiety” and others to describe their feelings felt them less strongly and demonstrated more brave behavior than others who didn’t use feeling words. Naming emotions helps us to manage them.

Name it to Tame it

As in my example of being in a room full of strangers, the task becomes learning the names of specific emotions and being able to use them (like remembering someone’s name when you meet them). First, we need to recognize the difference between a name and a nickname or colorful phrase.

First, naming a feeling starts with finishing the sentence, “I feel ____.” Notice you don’t use the phrase “I feel like ____.” That doesn’t give you a name; it only gives you a comparison. Here’s an example. Right now I feel confident. I could say “I feel like I’m going to finish my work early.” But there’s a difference. One is a feeling (confidence) and the other is a comparison (what confidence feels like to me).

Also, naming a feeling is something you truly feel, not something you think. If I say, “I feel okay” or “I feel good” or “I feel you aren’t listening”, those are all thoughts or judgments and not actual feelings. I think I’m okay or all right or that you aren’t listening, but those are not my actual emotions. If you catch yourself saying, “I feel you _____” then you’re capturing a judgment or opinion, not a feeling. Also, we tend to decide that some feelings are good and others are bad, or some are desirable and others aren’t. These are judgments and they interfere with actually naming what we’re feeling.

How do we learn to use more feeling words?

You can find lists of words online just like I started with a list of over 150 feeling words. But the list I had was not organized very logically and the sheer number was overwhelming to me in the beginning. If you are starting out, a smaller set of words is actually more management in the beginning. As few as 8 and up to 50 would be my recommendation. You can soon move up to more extensive lists of over 100 words or even 500 words. If you want some ideas you can start here.

Many people find a feelings wheel is even more helpful. A well designed wheel has certain basic or core emotions in the center, and that’s a good place to start. It’s like learning the family name. You move outward to get more specific or granular which is similar to learning the first name or full name of an emotion. I have found some wheels have a fairly random arrangement and I prefer one backed by research and a proven psychological model like Plutchik’s wheel of emotion. I have found that an emotion wheel has helped me make up for lost time in learning the names and relationships between a good number of emotions.

The secret that therapists know and have practiced for years is when you name a feeling or emotion, you start to feel more in control and less tossed around by your emotions. Psychiatrist Dan Siegel coined the phrase “Name it to tame it.”

Whether you are learning to drive, facing a medical diagnosis or working out differences in your relationships with others, naming feelings is a powerful practice that will help you be successful.